In the intricate world of central banking, few tools wield as much influence over the U.S. economy as open market operations (OMOs). Conducted by the Federal Reserve (Fed), these operations are the cornerstone of monetary policy, allowing the central bank to steer interest rates, manage liquidity, and attempt to foster economic stability. But in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, traditional OMOs evolved dramatically with the introduction of quantitative easing (QE), a large-scale intervention that expanded the Fed’s arsenal with consequences that have an enduring impact as of 2025.

The Basics of Open Market Operations

At its core, open market operations involve the Federal Reserve buying or selling government securities, primarily U.S. Treasury bills, notes, and bonds in the open market. These transactions, executed through the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), directly affect the amount of money circulating in the economy. The goal? To influence the federal funds rate, the interest rate at which banks lend reserves to each other overnight, which in turn ripples through broader financial markets, affecting everything from mortgage rates to business loans.

Historically, OMOs have been the Fed’s go-to instrument since the 1920s, but they gained prominence in the post-World War II era. Before the 2008 crisis, the Fed used them primarily to fine-tune the money supply and keep the federal funds rate aligned with FOMC targets. For instance, during the 1990s, OMOs helped navigate economic expansions and mild recessions by adjusting reserve balances in the banking system.

How Traditional OMOs Work: A Step-by-Step Breakdown

OMOs operate on a simple yet powerful principle: injecting or withdrawing cash from the banking system. Here’s how it unfolds:

- Buying Securities (Expansionary Policy): When the Fed purchases Treasuries from banks or dealers, it pays with newly created reserves. This floods banks with excess cash, encouraging them to lend more. As a result, interest rates fall, borrowing becomes cheaper, and economic activity like consumer spending and business investment picks up. This is classic expansionary monetary policy, aimed at combating slowdowns or recessions.

- Selling Securities (Contractionary Policy): Conversely, selling Treasuries drains reserves from the system. Banks have less money to lend, interest rates rise, and spending cools helping to curb inflation or prevent asset bubbles.

OMOs come in two forms:

- Permanent Operations: These involve outright buys or sells that permanently alter the Fed’s balance sheet. They’re used for longer-term adjustments, such as reinvesting maturing securities or targeting broader financial conditions.

- Temporary Operations: Shorter-term tweaks, like repurchase agreements (repos where the Fed buys securities with a promise to sell them back soon) or reverse repos (the opposite), help manage daily liquidity fluctuations without long-term commitments. In 2019, for example, the Fed deployed temporary repos to stabilize reserves amid market stresses, ensuring smooth policy implementation.

Ideally, the benefit of OMOs lies in their precision and market-friendliness. Unlike direct rate mandates, they let the Fed influence rates indirectly through supply and demand dynamics, avoiding overt interference in private markets.

Enter Quantitative Easing: A Game-Changer

By late 2008, the global financial crisis had pushed the federal funds rate to near zero, rendering traditional OMOs insufficient in the eyes of the Fed. Enter quantitative easing, an unconventional twist on OMOs that marked a seismic shift in Fed strategy. QE isn’t just buying securities; it’s doing so on a massive scale to inject trillions into the economy when rate cuts alone can’t stimulate growth.

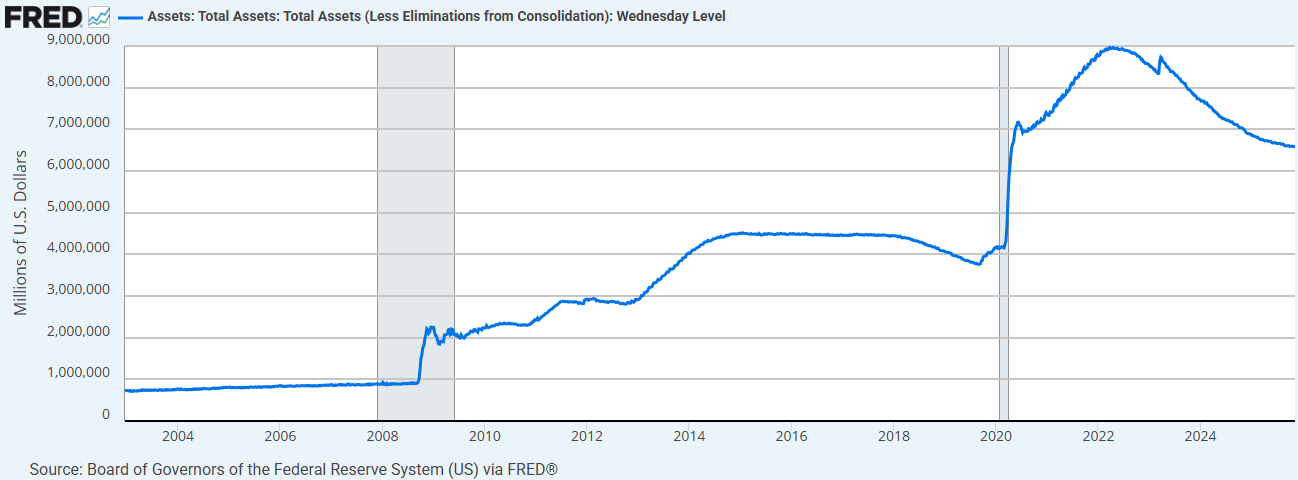

Launched in November 2008 as QE1, the program involved the Fed purchasing $600 billion in mortgage-backed securities and agency debt over several months. Subsequent rounds in QE2 (2010, focusing on Treasuries) and QE3 (2012, open-ended purchases) ballooned the Fed’s balance sheet from under $1 trillion pre-crisis to over $4 trillion by 2014. The COVID-19 pandemic revived QE in 2020, with purchases peaking at $120 billion monthly, pushing holdings to nearly 30% of U.S. GDP, at a whopping 8.9 trillion by the year 2022.

How QE Transformed Open Market Operations

QE didn’t invent OMOs, but it supercharged them. Traditional OMOs were like a scalpel, precise, short-term adjustments to short-term rates. QE, by contrast, is a sledgehammer: large-scale, long-term purchases aimed at compressing long-term interest rates and flooding markets with liquidity. Key changes include:

- Scale and Scope: Pre-QE, OMOs involved modest volumes (billions, not trillions) of short-term Treasuries. QE targeted longer-maturity bonds, mortgage securities, and even corporate debt in later iterations, directly lowering yields on 10- and 30-year loans to spur housing and investment.

- Balance Sheet Expansion: Traditional OMOs kept the Fed’s holdings stable; QE exploded them, creating “excess reserves” that banks could draw upon without tightening credit. This shifted policy from rate-targeting to quantity-targeting, where the Fed committed to buying fixed amounts regardless of market conditions.

- Economic Impacts and Trade-Offs: QE boosted stock markets, eased borrowing costs, and attempted to support a recovery. However, U.S. GDP grew by only 2.5% annually post-QE1. However, it widened wealth gaps (favoring asset owners) and raised inflation fears, though actual price surges lagged and were muted compared to expectations. Critics dubbed it “money printing,” but it primarily swelled bank reserves rather than consumer wallets, which is why it never led to substantive spikes in inflation.

Post-2014, the Fed began “normalization” via quantitative tightening (QT), selling assets or letting them mature to shrink the balance sheet, reducing it by over $2 trillion since 2022 as of mid-2025. Yet QE’s legacy endures, as temporary tools like repos and standing facilities now complement permanent operations, hoping to provide backstops against modern shocks like pandemics or geopolitical tensions.

The Road Ahead: OMOs in a Post-QE World

Open market operations remain the Fed’s most flexible weapon. As of November 2025, with inflation cooling, the Fed is attempting to balance a gradual tightening using OMOs to navigate uncertainties like AI-driven productivity booms or supply chain fragilities. Understanding these tools empowers us to grasp not just policy mechanics, but how the central bank attempts to steer the world’s largest economy through the calm and stormy weather.

How Successful Was QE?

Critics suggest QE also birthed asset bubbles by distorting market signals and encouraging speculation. Low rates lured investors into riskier bets, from tech stocks to junk bonds, only for “Fed put” expectations to bail them out. A 2017 Bank for International Settlements study found QE boosted equities tenfold more than real output, hinting at frothy valuations untethered from fundamentals. In housing, post-COVID QE’s mortgage focus created rigid prices, with “lock-in” effects from low-rate mortgages slashing sales by 1.7 million units and prolonging inflationary pressures into 2025.

QE’s safety net presents other issues argues former Fed dissenter Thomas Hoenig. He suggests it breeds moral hazard, with banks and firms taking outsized risks knowing the Fed will intervene. This “allocative effect” funnels capital to Wall Street speculation over Main Street investment, as seen in corporate stock buybacks ($1 trillion annually post-QE) rather than hiring or R&D. Small businesses, reliant on floating-rate loans, suffered while giants locked in cheap debt.

Broader distortions include currency devaluation: QE’s liquidity flood weakened the dollar, hiking import costs and squeezing consumers. Banks, flush with reserves, often hoarded cash amid uncertainty, starving the real economy of loans, a “credit crunch” irony. The Cato Institute’s analysis describes this as excess stimulus gone awry, with QE’s asset buys mimicking fiscal policy and blurring lines between monetary stability and credit allocation.

QE Flood to Fed’s Bill: How Excess Reserves Sparked Massive Interest Payments to Banks

The explosion of bank reserves through QE fundamentally altered the Federal Reserve’s monetary plumbing, leading to a policy tool, interest on reserves that didn’t exist pre-2008. What started as a crisis response to inject liquidity has evolved into the Fed shelling out tens of billions annually to banks just for holding cash, a stark contrast to the lean-reserve era before the financial meltdown. This shift, while stabilizing, has drawn fire for its fiscal footprint, especially as rates climbed post-2022.

Before the 2008 crisis, the Fed operated in a “scarce reserves” regime. Banks held minimal reserves, typically $10–40 billion total across the system to meet regulatory requirements, with little excess. The Fed fine-tuned the federal funds rate (the overnight lending rate between banks) through OMOs, buying or selling Treasuries to adjust reserve supply. This meant no need to pay interest. Banks had incentive to lend out any surplus to earn returns, keeping rates in check. Annual interest expense? Effectively zero, as the Federal Reserve Act didn’t authorize it until later.

The 2007–2009 crisis changed everything. With the federal funds rate slashed to near zero (0–0.25%), traditional OMOs couldn’t stimulate further without negative rates, an uncharted territory. QE flooded the system with excess reserves of cash that banks didn’t need for requirements but couldn’t easily “unpark” without selling assets back to the Fed.

By 2014, reserves hit $2.5 trillion; they peaked at over $4 trillion in 2021 amid COVID QE. Today, under the “ample reserves” framework, banks hold about $2.85 trillion in total reserves, with most qualifying as excess. Without a mechanism to manage this glut, the federal funds rate would collapse toward zero, as banks dumped reserves into overnight loans, eroding the Fed’s control over borrowing costs economy wide.

The Fix: Authorizing Interest on Reserves to Stem the Tide

To avoid draining reserves (which could tighten credit and harm recovery), Congress granted the Fed authority to pay interest on reserves via the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 (EESA). This kicked off October 1, 2008, for required reserves and expanded to excess reserves in 2011 after Dodd-Frank tweaks. The rationale? Paying interest creates a “floor” under short-term rates: Banks won’t lend below the IOR rate (since they can earn it risk-free at the Fed), helping target the federal funds rate without active reserve management.

How It Works: The Fed sets the Interest on Reserve Balances (IORB) rate currently 3.90% as of November 13, 2025, just below or at the fed funds target (3.75–4.00%). Banks earn this on all reserves held at Fed accounts. It’s automatic: No application needed; it’s like a high-yield savings account for banks.

QE’s Direct Link: Without QE’s reserve surge, IOR would be irrelevant, pre-crisis volumes were too small to justify the policy. QE forced the “ample reserves” regime, where IOR became the primary tool for rate control, replacing daily OMOs.

This setup completely flipped the script. Instead of banks paying the Fed (via required reserve penalties), the Fed now subsidizes them. How much does the Fed subsidize them? Today the Fed’s interest payments to the banks on excess reserves are in excess of $110 billion annually. In 2024, total US bank profits were approximately $268 billion. That means that more than 40% of bank profits now come from interest earned from money just parked with the Fed.

The Great Unwinding

If QE’s launch was bold, its exit via QT has been bumpy, amplifying critiques. Shrinking the balance sheet risks liquidity crunches, as seen in 2019 repo spikes and 2024 market strains, forcing the Fed to slow QT in May 2024. Reserves at 10–11% of GDP signal more than “ample” levels, but abrupt tightening could spike rates and instability. Many fear it perpetuates addiction to easy money.

As the chart above demonstrates, the Fed balance sheet today, nearly two decades after the financial crisis, stands at more than 6.5 trillion dollars, more than 7 times what it was pre-2008. It is beginning to appear as though the Fed has no intention of fully “normalizing” the balance sheet back to a pre-financial crisis level.

About the Author

Joseph M. Favorito, CFP® is a Certified Financial Planner® as well as the founder and managing partner at Landmark Wealth Management, LLC, a fee-only SEC registered investment advisory firm. He specializes in helping individuals and families develop comprehensive financial strategies to achieve their long-term goals.