Inflation Today: What is it Really?

In February of 2015, we wrote an article about the topic of inflation that tried to address not only some of the concerns about inflation, but also some of the confusing and seemingly misleading inflation data. Particularly, how the measures of inflation have changed over the years to reflect what may be a very inaccurate picture for a large number of Americans.

Let’s start with a little history. Inflation measures were traditionally designed to measure a constant standard of living. This was done by observing a fixed basket of goods and measuring the price changes without materially altering their weighting. In fact, prior to 1945, what we now call the Consumer Price Index (CPI) was actually known as the Cost of Living Index.

However, this concept evolved in academia to measure a constant level of satisfaction. The idea was that the changing relative costs of goods would lead consumers to substitute less-expensive goods in place of more-expensive goods. If such a substitution of goods was allowed for within what was once a model of a fixed-basket of goods, the maximization of the “utility” of money held by consumers would allow for the attainment of “constant level of satisfaction” for the consumer. These types of geometric weightings are now the method of choice.

In more simple terms, if consumers were once eating steak three nights a week, but the cost of steak has grown, and they are now relegated to buying a less expensive set of goods such as pasta, then pasta would increase in the weighting of the CPI since it is more actively consumed. This is essentially how CPI is calculated today. The more something is consumed, the bigger weighting it will eventually have. This was seemingly viewed as a positive change in academia as the presumption is that the level of satisfaction is the same because a less expensive product is being used to meet the same need and expanding the “utility” of money.

The utility of money is defined as “the satisfaction of or benefit derived by consuming a product”. These types of interpretations may seem quite nebulous to the layperson. In the example above, there may be some people who are just as satisfied by eating less expensive pasta rather than spending their money on steak, while others may not be so pleased by this outcome, and don’t particularly like pasta. It is for that reason that we would argue that some of the inflation data is misleading versus the real-world experience.

Recently the Bureau of Labor and Statistics announced that beginning in January 2022 it will be changing the weightings in the Consumer Price Index to reflect the 2019/2020 consumption expenditure data.

Many changes have been made to the methods of calculating inflation over the decades. Economist and economic consultant Walter J. Williams has written about this for years. Using his inflation models, he contends that if we were to use the same formula that was used in 1990, the rate of inflation is in excess of 10% as of November 2021. He also has models using the 1980 based methodology which places current inflation closer to 15%. Perhaps, the new models are more accurate. That would then by process of elimination mean that the higher inflation seen in the late 1970’s to the early 1980’s was not as bad as we thought. However, we think those who lived through that period would likely disagree.

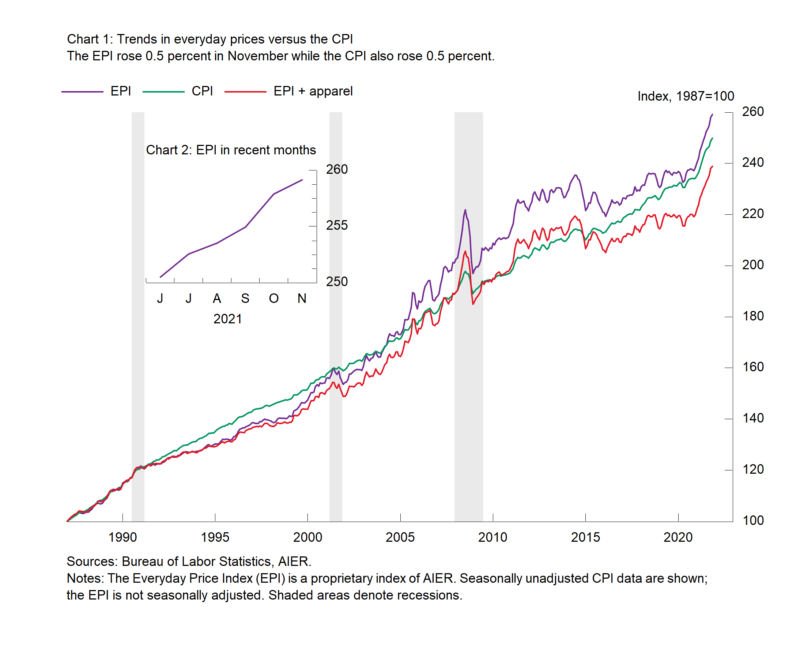

The American Institute for Economic Research maintains an inflation calculation created by two economists, Polina Vlasenko and Steven R. Cunningham, called the Everyday Price Index (EPI) which is designed to look closer at the consumers reality. The premise is that they essentially place heavier weightings on the items that are purchased more frequently, such as grocery shopping, and less of a weighting on items that are bought less frequently, such as a new television. As seen in the above chart, through November of 2021 the EPI was at 9.3% versus the governments CPI data of 6.8%.

Another change that has resulted in a significant difference in the way inflation was calculated in the 1980’s data versus today, is housing. House price inflation was included as a metric then, while today it is not. As Joseph Carson, the former Chief Economist for Alliance Bernstein recently noted this past July 2021:

“Here’s a simple illustration of how significant including and not including house price inflation can be. In 1979, CPI rose 11.3%, and that included a 14% increase in the price of existing homes. In the past twelve months, CPI has increased 5.4%, and the 23% increase in existing home prices is not part of that. Government statisticians have created an arbitrary owner rent index (up 2.3% in the past year) to replace house prices.”

The case for not including housing was that it is a long-lived asset that the consumer will consume for a series of years or perhaps decades. Yet, while home prices are excluded, short lived items like food and energy are also excluded from the Core CPI. Meanwhile used car and truck prices, which can have a ten-year life span have a 3% weight to the CPI. If you are a potential new home buyer, this may seem somewhat disconnected from reality.

Another variable in the CPI data is that there is more than one version of the CPI. CPI-U measures the rates of inflation for urban areas, and CPI-W measures the inflation rate for clerical workers. These two are used to determine the annual increase in Social Security payments. One of the most commonly quoted measures of inflation is called the “Core CPI” which excludes the impact of food and energy products, which explains a good degree of the discrepancy between the CPI and Everyday Price Index (EPI). The premise for excluding them is that food and energy are extremely volatile and don’t represent the true picture of aggregate economic demand. Unfortunately, people still need to eat, heat their homes in the winter and fill up their gas tanks. As a result, it’s not too difficult to see why many people still believe that inflation data, which has been on the rise still doesn’t represent their real-life experience.

Hedonic adjustments are another aspect of how inflation data can be misleading. Hedonic adjustments attempt to measure the quality changes in a product or service. Imagine if a new computer increases in price by 5%, and the computer was exactly the same, that would mean it reflects inflation of 5%. However, if the quality of the computer has changed, and you are paying 5% more in price for a computer that has 10% more capability, then a hedonic adjustment may assume that the computer is selling for 5% less because you are getting more for your money, even though you spent 5% more in price. While in some cases this can make sense, what if the new added capability is of zero use to you, but that is all that is available in the marketplace? Have you really seen a reduction in price? Not necessarily. However, in the eyes if the Bureau of Labor and Statistics (BLS), that can be a reduction in cost via a hedonic adjustment. We see positive and negative adjustments all around us. The question is whether the BLS captures all of the boxes of cereal that sell for the same price, but now have a smaller box? This seems unlikely. It sometimes seems as though they capture the positively impactful adjustments whether they are relevant or not, and miss some of the negatively impactful adjustments.

At this point in time there are several drivers of inflation. Supply chain disruptions still resulting from the government shutdown, an unprecedented expansion of the M2 money supply, and higher energy prices. While supply chain problems will likely resolve over the next year, the other two issues may be with us awhile. The money supply has grown by 33% in one year versus a normal 6% annual increase. Energy prices have increased substantially, which translates into cost push inflation, and any significant capacity expansion in US energy seems unlikely in the next few years.

We have never been convinced that this particular period of higher inflation is as temporary or “transitory” as the Federal Reserve initially implied. It is beginning to seem that they are finally arriving at that conclusion as well. Or, they always believed this to be the case and did not wish to make it a public statement.

We would contend that each individual should essentially have their own personal inflation model based on their own behaviors. However, that is not terribly practical for the Bureau of Labor and Statistics. As a result, we believe this places a greater importance on financial planning, particularly for those closing in on retirement who will not have increasing wages to go along with increasing prices. Having a greater understanding of where your spending is headed based on your lifestyle goals is a key part of a well-designed financial plan. As inflation continues to climb, this is something at Landmark we try to address for all clients with a look towards their longer-term plans.