“Timing the Market” vs “Time in the Market”

Investing can be a very emotional rollercoaster ride for many individuals. These emotions are inherently counterintuitive. The desire to sell during difficult periods can be quite strong. Additionally, the desire to put money to work when markets are doing well can be equally as strong. These emotions often lead investors to sell low and buy high, which is precisely the opposite of what they should be doing.

Ultimately, the ability to time the correct entrance and exit into financial markets has proven to be an ongoing exercise in futility. The data around market timing consistently demonstrates this to be the case. There are many examples of this. The annual Dalbar studies demonstrate year after year how the average investor underperforms the overall market due to these types of poor decisions around timing. Additionally, the Standard & Poor’s Index Versus Active Management report (SPIVA) consistently shows that professional money managers demonstrate a very poor track record of outperforming markets as well, with roughly 90% of mutual fund managers failing to outperform their benchmark.

Additionally, a landmark study “Determinants of Portfolio Performance” done in 1986 by Gary P. Brinson, CFA, Randolph Hood, and Gilbert L. Beebower revealed that approximately 90% of your investment return comes from the overall allocation of assets, and has less to do with individual security selection. The importance of this paper helped reinforce the earlier work of economist Harry Markowitz and his research in 1952 on Modern Portfolio Theory, for which he was later awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics.

Today, we see data that suggests little has changed. The ability to time markets is as difficult as ever, and the importance of staying invested as opposed to timing the market is no different than in decades past.

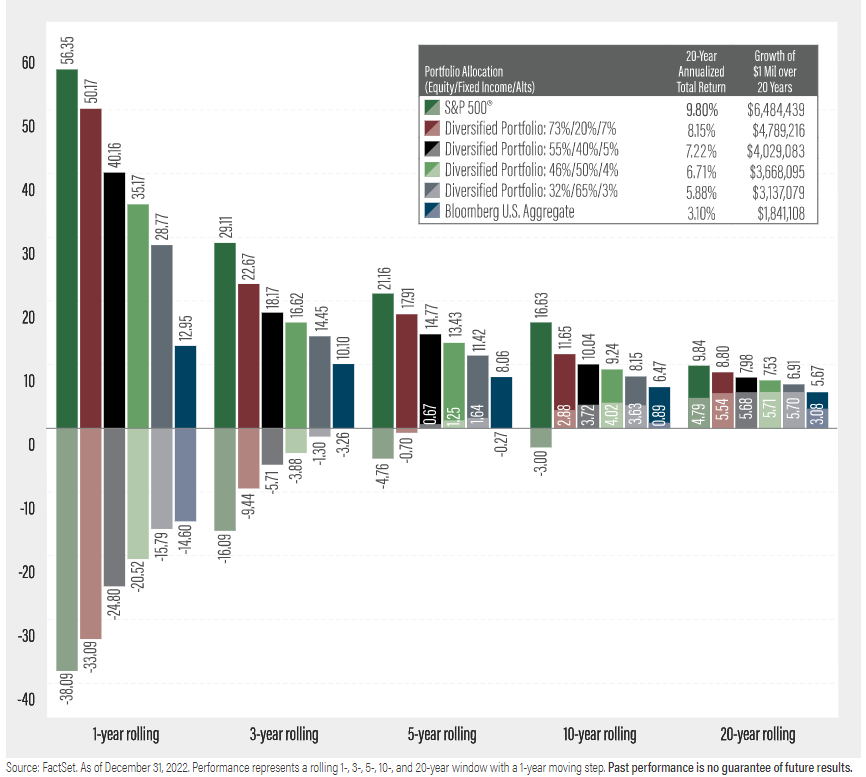

Looking at some recent data on asset allocation in the above chart, we can see the 1-year, 3-year, 5-year, 10-year and 20-year rolling returns for various asset allocation models. What we can see from the data is that the longer you are invested, the better you’ll do. While that should be no surprise to anyone, what we can also see is the probability of posting a negative period is much lower as you reduce exposure to stocks and increase exposure to fixed income.

Looking at the data we can see that a portfolio that is approximately 55% stocks has seen few negative 3-year rolling periods. In no circumstances were the 5-year or more rolling periods negative.

When looking at an investment portfolio that has a 73% exposure to stocks, we see a very nominal potential decline in any 5-year rolling period, with the overwhelming number of periods producing positive results.

When we expand the time frame to 10-year rolling periods, none of the asset allocation models have demonstrated any negative rolling periods, with the exception of being 100% invested in stocks via the S&P 500. It’s also important to note that even in the few examples in which the S&P 500 posts a negative 10-year period, this is an example that illustrates only price return, and does not factor in the dividend income from investing in the S&P 500. When we correct for the dividend cash flow generated, the worst negative 10-year periods actually go from negative to positive.

This chart demonstrates several important points.

- The likelihood of success by staying invested improves dramatically over time.

- The more of a balanced portfolio you have, the less likely you are to experience a negative result, even during a relatively short period of time.

- There is a point of diminishing returns in which the degree of increased short-term risk and volatility does not produce an equivalent increase in long-term return.

It is often said by the novice investor that “the stock market is like going to a casino”. In fact, the opposite is actually true. When you enter a casino, you may get lucky and win in the short-term, but if you stay long enough, the probability is you will lose as the odds are very much in the casino’s favor. Investing is precisely the opposite. You may very well see a negative return within the first year or two. However, the probability that you are still losing money within a 3-5 year window of time is very low. As investors, if you are disciplined enough to stay invested, you are essentially the casino owner as opposed to the gambling patron.