Social Security: Will the Gov’t Run Out of Money?

Will Social Security be there when I retire or will it run out, this is one of the more common concerns heard from clients in financial planning circles for years. The question is, should you legitimately be concerned? The answer is both YES and NO.

The concern about your Social Security payments ceasing because of the trust fund running out is likely an unrealistic concern. However, there are some legitimate serious concerns about the impact of social security and other entitlement programs, and how they might impact you.

Let’s start with why the payments won’t likely stop. The Social Security trust fund is made of what is called intragovernmental debt. The money that goes into the fund via payroll taxes from you and your employer’s contributions is invested in US government debt, which of course is an obligation of the taxpayers of the United States anyway. In 1968 beginning with the 1969 budget, Social Security became part of the Unified Budget Process. This meant that the receipts and outlays of the trust fund became part of the overall Federal budget. In the 1990’s Budget Enforcement Act these receipts and outlays were again segregated for accounting purposes.

In order to understand this better, one needs to really understand the basics of money creation. In reality, the Federal government has historically spent more than it collects in most years for all budget items, not just entitlements. In the eyes of most people, spending more than you collect is a significant problem. In terms of how a national government works, it can be a problem but doesn’t necessarily have to be.

The United States and every other nation now use what is called a fiat currency system, as well as something known as Fractional Reserve Banking (FRB). In simple terms, in a fiat system imagine if the Federal government in a given year spends $10 in the Federal budget, and simultaneously collects $7 in taxes. That means that $10 was pushed into the economy somewhere, and $7 was taken back out. Simple math tells us that there is now an additional $3 circulating in the economy somewhere. That additional $3 is part of the annual deficit. An additional $3 is issued in US treasury bonds in its place and added to the debt. What we can see from this process is that not only does the government simply create money out of thin air, but the deficit is necessary to help expand the supply of money. Since the government can in reality, not just in theory create an unlimited amount of money, the risk of running out of money is not really a risk. In fact, under the current system in place for more than a century, all money is created from debt. Furthermore, if you reversed the process and collected more in taxes than the government spent on a perpetual basis, also called a surplus, you would eventually run out of money. This is because you would be constantly pulling more money out of circulation than you are putting into circulation. So, running out of money is not technically possible, because the government can in fact create money at infinitum. The government would have to choose not to pay an obligation.

The monetary system is much more complex than this. The government has more than one way to create money. They can also create money via the Federal Reserve through what is called Open Market Operations. The Federal Reserve can also create money out of thin air, and then go and buy government bonds from institutions and individuals. The bonds they buy puts more cash into circulation, and the Federal Reserve then holds those bonds to maturity. Any profit they make on the purchase of these bonds is then returned to the US Treasury. This type of activity creates more money in circulation, but doesn’t directly service the US budget obligations. The direct spending authorized by the US Congress is what essentially pays the bills. Remember that in any given year, the budget numbers are determined the prior year in advance of the known tax revenue, and entitlements like Social Security are not even negotiated as part of the budget process, as they are mandatory non-discretionary spending.

Does this then mean that there is nothing to worry about? The answer is NO. There is plenty to worry about. Even though a government doesn’t “run out of money”, as we have seen throughout history, too much money creation can be a substantial problem. A little more than a decade ago we saw a sovereign debt crisis spread across Europe. Countries like Greece, which was among the most fiscally impaired, never went bankrupt and never ran out of money. However, a nations debt is dependent on the market for people, corporations and other nations to buy and trust that debt as investors. When the buyers of the debt grow concerned, they demand higher interest payments, and maybe stop buying altogether. Nations like Greece were forced by their European Union counterparts to impose austerity on their fiscal budgets to bring them back into something more reasonable. It’s essentially the equivalent of having to pay higher interest rates on your credit cards because you have a bad credit rating, which only further compounds your problems if you don’t correct your spending habits.

Furthermore, under the Fractional Reserve Lending (FRB) system, which is the banking process globally, things get more complicated. What is defined as money isn’t always entirely clear. The Federal government legally is the only entity that can officially create money. When the government spends and creates money, this gets added to what is called the Monetary Base. The Monetary Base is a measure of the cash circulating in people’s pockets, plus the cash reserves held by banks. However, banks can lend out at a ratio of about 10:1 for each dollar they have in reserves. When you go to the bank to get a car loan, they don’t take their reserves held in someone else’s savings account and lend it to you. They effectively also create money out of thin air via extending credit. The bank will create a digital dollar and loan it to you, which you then spend somewhere else, and someone else will deposit elsewhere. The loan creates the deposit, rather than the other way around. That loan becomes an asset to the bank, while your bank deposits are actually a liability to them. This credit expansion is part of what is called the M2 money supply, which is a broad definition of how much money is in circulation. Banks can lend out about $100 dollars for every $10 dollars in reserves.

Each time you borrow money, you expand the M2 money supply. Each time you make a debt payment, the loan is reduced or extinguished, and you shrink the M2 money supply. If there are more people wishing to borrow money than the banks reserves currently allow for, they can borrow from another bank’s reserves. If the banking system as a whole doesn’t have enough in reserves to meet the demand, they simply go to the Federal Reserve and borrow more money, which the Federal government creates for them. They can then lend out another $10 for every $1 the government lent them. Technically, the government can choose not to lend the bank this money and constrain banking reserves to restrict the money supply. However, in reality this doesn’t happen. If there is consumer demand, the Federal Reserve will meet that demand. This means a big part of money creation is based upon simply how much the public wishes to borrow. This is something in economics known as “Endogenous Money”.

So why is this something to be concerned with? The answer is too much money creation in excess of goods and services being produced means inflation, which is something we are seeing at the moment and addressed in our prior article on December 14th, (Inflation Today: What is it Really?). The gov’t has the ability to quickly change policy on things like expanding banking reserves through lending or bond buying. However, Federal spending on entitlements is mandatory. It is also an ever-growing portion of the Federal budget.

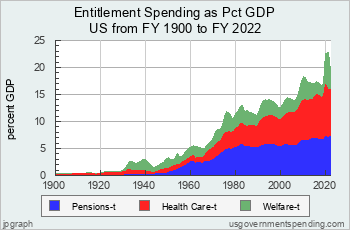

As you can see from the chart above from www.usgovernmentspending.com, entitlement spending as a share of GDP has grown enormously from 0.4% of GDP at the beginning of the 20th century, to 22.8% of GDP today. It also represents more than 50% of the current Federal budget, versus only 15% of Federal spending at the end of World War II.

More concerning is the unfunded future liabilities, which according to the US Treasury are now more than 161 trillion dollars in future promised benefits. That means we have promised benefits that are approximately 7 times the size of the current US economy, and about 7.5 times the amount of the total M2 money supply. This growth in spending means the total debt to GDP ratio has grown from 55% to over 125% today since the year 2000. There is a good degree of research that suggests that once an economy passes around a 90% debt to GDP ratio, slower economic growth is likely, as the cost to service the debt smothers future productivity. Essentially, the government begins to spend more money on things like entitlements, and less money is directed towards new innovations or more productive use. We are already well past that 90% ratio.

This doesn’t mean that this won’t go on for some time. Japan as an example has grown it’s debt to GDP ratio from 75% in 1992 to over 260% today. While that, plus some major demographic challenges has led to extended periods of incredibly slow growth, they also did not “run out of money”.

This is also not a problem which we can tax our way out of, as tax revenue is fairly consistent. As per the Tax Policy Center, total tax revenue is consistently between 15-20% of GDP since the end of World War II. During periods of expansion, the treasury tends to collect more in revenue, and during periods of recession it collects closer to the lower end of this range. This was true when the top marginal rate was over 90%, and as low as 28%. As an example, here is a comparison of 1946 versus 1988:

1946

The top marginal rate for an individual was 91%, and for a corporation 38%.

The total revenue to the US Treasury from all sources was 17.2% of GDP. Approximately 7.1% of GDP came from individuals, and 5.2% of GDP came from corporate income tax. Payroll taxes accounted for 1.4% of GDP. The rest came from various other sources to the treasury.

1988

The top marginal rate for an individual was 28%, and for a corporation 34%.

The total revenue to the US Treasury from all sources was 17.7% of GDP. Approximately 7.8% of GDP came from individuals, 1.8% of GDP came from corporate income tax. Payroll taxes accounted for 6.5% of GDP. The rest came from various other sources to the treasury.

If you look closely, you can see that the total revenue to the Treasury was actually higher in 1988, although within the normal range of tax revenue as a share of GDP. It’s also worth noting that corporate income taxes contributed a much smaller percentage to GDP. However if we compare these two periods, we can see that payroll tax revenue, which funds social entitlement programs rose by 5.1% of GDP. Since employers must pay 50% of the payroll tax liability, their combined contribution was still about 4.4% of GDP. Additionally, since the creation of S-Corps and LLC’s as “pass thru” entities for small business owners with less than 100 employees, more business are filing their taxes as personal income rather than corporate income. What you can see is that employers are paying effectively similar percentages in taxes, they are just paying it under a different column in the tax revenue ledger. Tax revenue has not changed substantially, but spending has risen dramatically. In fact, some of the highest tax nations in the developed world face even greater fiscal challenges from their entitlement programs.

Ultimately, entitlement benefits must be cut at some point in time. Whether that is because the US government reaches a point not unlike Europe’s sovereign debt problem in which the rest of the world via the debt markets forces us into austerity, or because our elected officials finally come to the conclusion that this is an unsustainable path is hard to predict. The latter seems unlikely at the current moment. In the political world, once the toothpaste is out of the tube, it’s very hard to put it back in. Nobody seems to want to run for office promising to take away one of your benefits. Even if they did, they are not likely to get much cooperation from their counterparts in Washington D.C. at this point.

What will these cuts look like, and when does this happen? Well, nobody knows for sure. However, we think Social Security is the easiest to address of all the entitlement programs where some relatively minor changes could make a big difference. Simply raising the age of full benefits is one possibility, as well as even raising the age of early benefits. When social security was first created the average life expectancy was substantially lower, and they never expected to pay people as long as they are now. The system was not actuarily designed for people to live as long we do today, and should be corrected to reflect longer life expectancies.

Another possibility, although less popular is means testing benefits. However, future taxpayers may not like the idea of paying into a system for decades that is designed to supplement their retirement, and then getting nothing in return if they exceed a certain asset or income level set by Congress. Yet, that does remain a future possibility. There are other possible solutions, and it may be a combination of things.

However, it still remains highly unlikely that Social Security will just stop for anyone currently collecting or close to collecting benefits. It is not unlikely that younger generations at some point will see a benefit system that doesn’t pay out at the same rate the current system pays.

The timing of when these issues will get addressed is nearly impossible to predict, and will depend on a confluence of events that nobody can accurately time. In order to truly understand why your benefits won’t likely just cease, its important to understand that a national budget is very different than that of a household budget, and governments don’t just run out of money the way you or I can. Still, history tells us that while govt’s can create unlimited amounts of money, it is not without potentially serious consequences. Unfortunately, it often seems that the very reason that the government can’t run out of money is precisely what drives so much rapidly increasing and often reckless spending. Perhaps the Federal government could learn a thing or two from the average citizen about proper budgeting.